I read somewhere that in

his will William Shakespeare left his wife his second-best bed. I’ve never

found any of my ancestor’s wills. Hardly surprising because they were ‘common

folk’, ag labs and the like. What they did bequeath the future generations was

their DNA, though I have yet to discover a DNA match with another Hall family

descendant.

I wrote of Mary Ann

Smith in response to the week 13 prompt ‘Nearly Forgotten. Mary Ann married my

great grandfather Thomas Hall and this is his story.

Thomas was born in

Peterborough 5 August 1846 to William Hall and Elizabeth (Hinson), the youngest

of at least six children all born in Crowland. William born 1834, Elizabeth

born 1836, Samuel born 1838, Ann born 1841, and Joshua born 1843. There is a

possible baptism for Thomas 16 Aug 1846 at Saints Mary Bartholomew and Guthlac.

I took this photograph of Saints Mary Bartholomew and Guthlac in 2014.

Crowland/Croyland has an interesting history.

Originally the area was wild marshland crisscrossed by causeways and meandering

rivers. St Guthlac chose one of the small

‘islands’ as a retreat, which by the eighth century had become an important monastic

site and the surrounding small village had grown into a significant market town.

Peterborough was part of Northamptonshire until 1888.It

then became an independent administrative county known as 'Soke of

Peterborough'. From 1965 it merged with Huntingdonshire to be county of H &

P and from 1974, along with Hunts, is contained in Cambridgeshire, that being

said, on Ancestry every census 1851 - 1901, Peterborough is in County of

Northamptonshire.

The 1851 census is the first to list Thomas, aged four.

His father’s occupation was ‘ag lab’ and they lived in Poor House Lane in the district

of Croyland, Peterborough. I modern times the street was renamed Albion Street.

1889-1891 map showing the position of

the Abbey.

On the 1861 census Poorhouse Lane has become Poors lane. Thomas now aged

14, occupation, basket maker. I am sure that this is the correct family as the

neighbours are the same as those on the previous census. At 7 Poors Lane are

Richard and Mary Cooke, daughter Susannah then aged 21 aged (Thomas’s brother William’s

future wife) and grandson John T Cooke, aged 3 (was she a single mum.?) also

living in this house was a 71 year old lodger, Samuel Beekin, formerly a

butcher. Interesting

to note that on this census just a few doors away at 9 Poors lane is a family

called Hinson, the maiden name of Thomas’s mother Elizabeth. Could the head of

this household, Peter Hinson, be Thomas’s uncle, that is his mother’s brother?

I struggled to locate Thomas on the 1871 census. His parents William

and Elizabeth were at home at 90 Poors Lane. Next door at number 91 Poors lane

are the following.

Richard

Cooke, Head, widow aged 69. Occupation Ag Lab.

William

Hall, son in law, aged 35 Ag Lab, is this Thomas’s brother?

Susannah

Hall , daughter aged 31

Mary E

Cooke Granddaughter aged 8

John T

Cook Grandson aged 12

These two

children raise the as yet unanswerable question, were they Susannah’s

illegitimate children?

This is probably him at in Crowland on the 1871of the right

age and occupation, but only possible. After quickly searching Israel Lyn on

Ancestry I found that the married name of his wife was Hall. More research on that will have to wait for

another time.

Below is the transcription

During the 1840’s the Great Northern Railway Company

opened main trunk lines between London and York, Peterborough lying halfway

between London and Doncaster went from a market town to an industrial centre

with a railways major repair and maintenance depot. The impact of this

industrialisation can be clearly seen in the change of occupations for Thomas

from ‘basket maker on the 1861 census to engine fitter on the 1881.

The opening up of transport links obviously created easy

travel to the capitol city where Thomas and Mary Ann’s children were born as

was Mary Ann herself. So did Thomas travel to London in search of work and met

Mary Ann there.

I also looked for where his brothers William, Samuel and

Joshua had gone to.

Joshua, according to 1901 census continued in the same

trade that young Thomas had, that of basket maker, working at home on his own account

He married Sarah from Northants and that is where he was living on this census,

with daughter Kate 18 and son Arthur 7. East Northants, Wellingborough. William

married Susannah Cooke 24 Oct 1870, and it is in the 1871 census that we find

him living with his wife and father in law next door to his parents. William’s

death occurred before the next census of 1881. On census records I found Samuel

and his wife Ellen in North Frodingham, Yorkshire, England.

There he is on the 1881 census at 158 Botolph Road,

Bromley, Tower Hamlets, occupation, engine fitter labourer. Also at home were

wife Mary Ann with children Eliza, Ada, and Alice all listed as scholars, and my

grandfather young Herbert Henry aged one. The sisters, Herbert, and younger

brother Joseph appear to have been born in Bromley, but I have yet to locate

any baptismal records for them or the younger brothers Arthur and Frederick who

were born in East Ham

1881 England

Census for Thomas Hall, London, Bromley Leonard

As an engine fitter

labourer Thomas may have worked on the railway as among his neighbours was a railway stoker, an engine driver railway, a

railway guard and a railway engine

fireman. As was usual for the time

there is no mention of an occupation for his wife Mary Ann who, with a husband

and four young children to keep house for, may well have found the time and

energy to do things like take in washing or other domestic work to supplement

the household income. She could even have worked in one of the many local

industries.

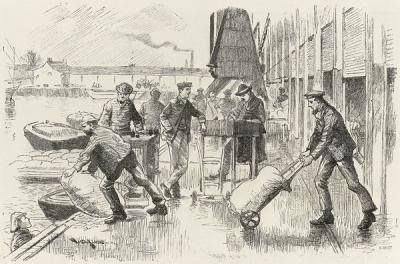

Whatever Thomas’s place of work was there can be no doubt that it would have been affected by the Great Dock Strike that began on august 12th 1889, young Herbert Henry, my grandfather, would have been about ten years old. The strike, over conditions of work and rates of pay, lasted for about five weeks. Industry owners were at first confident that they could starve an end to it, but when funds of more that £3,000 arrived from Australia they must have known they were beaten. The strike succeeded and almost every one of their demands were met.

Whatever Thomas’s place of work was there can be no doubt that it would have been affected by the Great Dock Strike that began on august 12th 1889, young Herbert Henry, my grandfather, would have been about ten years old. The strike, over conditions of work and rates of pay, lasted for about five weeks. Industry owners were at first confident that they could starve an end to it, but when funds of more that £3,000 arrived from Australia they must have known they were beaten. The strike succeeded and almost every one of their demands were met.

On the 1881

census but at 92 Poors Lane in Crowland is Elizabeth Hall aged 76 with daughter

Elizabeth Baker aged 44, both widows, daughter’s occupation is listed as ‘Nurse

SMS’. I think that Elizabeth Hall was Thomas’s mother and the younger Elizabeth

his sister. Remember the Baker family from the 1871 census.

1891 census 29 Cypress Place,

Manor Way, Bromley, Thomas’s occupation now listed as a labourer general

You can read more about Thomas and Mary Ann in the piece I wrote about her called 'Nearly Forgotten'.

The family remained at the same address for the next

ten years, and it was during this time that Thomas passed away, I have yet to

locate his death date. As with other census records there is no occupation

listed for Mary Ann, but she would almost certainly have had some sort of

occupation. It was common for the time to consider that women’s work of household

duties prevented them from being in other employment. Women took in laundry, did

piece work at home or did domestic work in other houses.