In Search of Granddad

It’s not until I began to put the facts together about Granddad that I realised how little I really know about this man, Herbert Henry Hall, my mother’s father.

It’s not until I began to put the facts together about Granddad that I realised how little I really know about this man, Herbert Henry Hall, my mother’s father.

When he was born on the third of October 1879

his parents Thomas and Mary Ann, formerly Smith, Hall already had three daughters,

Eliza aged seven, Alice aged five and four one-year old Ada. They lived in

Bromley St Leonard, slightly north of the Thames, in London’s East End, not to

be confused with Bromley in Kent, and it was changing.

For some, the words ‘East End’ conjure up images from Charles Dickens books. Of poverty and disease, slums and crime, sweatshops and rogue landlords. In many parts of the East End those conditions certainly existed, but the prospect of employment at the nearby docks and the industries surrounding them drew people like a magnet. From the 1820s, Bromley began to fill with noxious industries and workers’ housing, some built by charities, some by profiteering jerry builders. Much of Bromley was a slum by the late 19th century and it became an early target for civic improvement

For some, the words ‘East End’ conjure up images from Charles Dickens books. Of poverty and disease, slums and crime, sweatshops and rogue landlords. In many parts of the East End those conditions certainly existed, but the prospect of employment at the nearby docks and the industries surrounding them drew people like a magnet. From the 1820s, Bromley began to fill with noxious industries and workers’ housing, some built by charities, some by profiteering jerry builders. Much of Bromley was a slum by the late 19th century and it became an early target for civic improvement

Between 1801 and 1881 the population in the

area increased almost fourfold to nearly five thousand. What had been an area of farming and market

gardening was rapidly becoming industrialised. Fields gave way to factories and

workers houses; old country lanes were replaced with streets lined with

terraced houses of yellow brick.

The first mention of Herbert Henry Hall in public

records, apart from his birth, is on the 1881 census at 15 St Botolph Road, Bromley,

along with his parents and older sisters. His father Thomas’s occupation was

that of engine fitter labourer. Did Thomas perhaps work on the railway for

among his neighbours was a railway stoker, an engine driver-railway, a railway

guard and a railway engine fireman.

As was usual for the time there is no mention of an occupation for my grandfather’s mother, Mary Ann, who, with a husband and four young children to keep house for may well have found the time and energy to do things like take in washing or other domestic work to supplement the household income. She could even have worked in one of the many local industries. Grandfather’s sisters were all described as scholars.

Whatever Thomas’s place of work was there can be no doubt that it would have been affected by the Great Dock Strike that began on august 12th 1889, young Herbert Henry would have been ten years old. The strike, over conditions of work and rates of pay, lasted for about five weeks. Industry owners were at first confident that they could starve an end to it, but when funds of more that £3,000 arrived from Australia they must have known they were beaten. The strike succeeded and almost every one of their demands was met.

As was usual for the time there is no mention of an occupation for my grandfather’s mother, Mary Ann, who, with a husband and four young children to keep house for may well have found the time and energy to do things like take in washing or other domestic work to supplement the household income. She could even have worked in one of the many local industries. Grandfather’s sisters were all described as scholars.

Whatever Thomas’s place of work was there can be no doubt that it would have been affected by the Great Dock Strike that began on august 12th 1889, young Herbert Henry would have been ten years old. The strike, over conditions of work and rates of pay, lasted for about five weeks. Industry owners were at first confident that they could starve an end to it, but when funds of more that £3,000 arrived from Australia they must have known they were beaten. The strike succeeded and almost every one of their demands was met.

Queen Victoria was on the throne and her

consort was Prince Albert. Unfortunately, he contracted typhoid and died in

1861, after many years in mourning she began to enjoy life again, discovering

an interest in in the many new inventions - the telephone, gramophone and

photography - and she traveled all over Britain on the railway. 1887 was her Fifty-Year

Jubilee, and she drove through streets of London, cheered by thousands.

By the time of the next census, taken on

Sunday April 5th 1891 the Hall family, now increased by several more children,

had moved to 29 Cypress Place, Manor Way, New Beckton. This address no longer

exits due to extensive bombing damage during WW II and the subsequent

rebuilding of London Docklands.

I thought that with a name like ‘New Beckton’

the move would have meant improved living conditions, how wrong could I have

been.

According to http://hidden-london.com/gazetteer/cyprus/

Cyprus, Newham

Cyprus’s name dates from 1878, when Britain

leased the Mediterranean island from Turkey. Also known as New Beckton, this

tiny settlement with its shops and services was a ‘self-supporting

community’, entirely owned by the Port of London Authority, providing homes for

workers at Beckton gasworks and the Royal Docks. Unlike the earlier workers’

housing in ‘old’ Beckton, construction standards here were not high and the

absence of mains drainage contributed to the poor health of the residents.

In addition to Herbert, now aged ten, and his

sisters were; Joseph and Arthur, aged eight and two years old, and four and a

half month old Frederick. Missing from this the 1891 census was young Thomas

Hall who, according to the later 1911 census, was born in 1887 so may have been

about four years old. The only likely birth I can find for him is in the

April-May-June quarter of 1887. That later census also give us his place of

birth and another potential address for the family, that of Roman Road East

Ham.

Despite searching for him elsewhere in the

1891 census I have so far been unable to locate him. I can only think that he

was perhaps staying with a relative. The only other Thomas Hall of the right

age on the census in the area is a three-year-old, but with Grandparents Henry

and Elizabeth Brown and that is not a name that appears in either of the

grandparents families.

Thomas’s occupation in 1891 had changed to

general labourer. Not ‘dock labourer’ as were many of his contemporaries, so

perhaps he worked in one of the local industries rather than on the docks

themselves. 1891 was a year of extremes of weather. February was recorded as the driest month,

followed just one month later by ‘The Great Blizzard’ that claimed 220

lives. In England’s south and west there

were extensive snow drifts, and powerful storms off the south coast sank 14

ships. That year also saw an act of

parliament that prohibited the employment of children younger than eleven

years.

Moving forward another ten years to the next

census taken on March 31st 1901, Herbert is now a young man of 21. We find him with his, now widowed, mother

Mary Ann as head of the household still at 29 Cypress Place. Of his siblings

only Joseph aged 18, Arthur aged 15, and Frederick aged 13 are at home. Herbert

and Joseph are the only ones with occupations listed, that of general

labourers, again there is no occupation for Mary Ann. Were his sisters off and

married, or in service somewhere, this is still to be determined, and where was

their brother Thomas?

January 22nd of that year heralded the end of

an era with the passing of Queen Victoria. After almost 64 years England’s

longest reigning monarch became unwell and died.

There were other great events that year too.

In August Robert Falcon Scott sailed off on the RRS Discovery to explore the

Ross sea in Antarctica and in December Marconi received the first transatlantic

radio signal. In Morse code the letter ‘S’ was sent from Cornwall to

Newfoundland.

In 1903 the Pankhurst sisters founded the

militant Women’s Social and Political Union in Manchester. Motor vehicles were

first licensed and number plates were introduced, as was a speed limit of 20

miles per hour in 1904. The first public protest of the Suffragettes occurred

in 1905, the same year that aspirin was first sold in the UK.

Herbert Henry Hall married Georgina Pirrett

on December 26th 1904 at the Catholic church of St Margaret’s and All Saints, 79

Barking Rd, London. Unlike his bride, Herbert wasn’t Catholic. On the copy of

their marriage certificate I have it states that they were married by ‘certificate’,

I have been told that the basic meaning of this was that any children born

should be brought up Catholic. Cousin Sheila, Mum's brother's daughter, remembered that Georgina ‘would

have a candle burning in the window at Christmas time, and woe betide anyone

who caused it to be blown out’.

On this civil registration of their marriage their addresses are 6 Burnham Street and 93 Forty Acre Lane. Their locations are displayed on the map below

I can’t find my grandfather on census night

Sunday 2nd April 1911 at 67 Denmark Street, Plaistow, so it is very likely he

was a sea. His wife and first child are

living there with her widowed mother and her mother’s sister. The entry tells

us that Herbert Henry and Georgina had been married for six years and had only

one child. Given the considerable gap between the marriage date and birth-date

of the eldest child it is probable that Granddad became a merchant seaman not

long after their marriage.

1911 Census

Herbert Henry (junior) was born in 1906,

followed seven years later by Veronica Ellen (Auntie Ron) in 1913, and then my

mother Georgina Mary in 1921. All three children were baptised at St

Margaret’s.

St Margaret's Church

Public records document his occupation

changing from general labourer (1891 census) to gas stoker (at his 1904

marriage) to merchant seaman (Port Kembla sinking 1917). Was it his prolonged

absences that that helped his wife become strong and resourceful or was it those

qualities in her that that drew him to her in the first place, we’ll never

know. Tattooed on Granddads arm were the letters I.L.G.P which stood for I love

Georgina Pirrett . More about her in another post.

Prior to existing shipping records the only

proof of times when he was at home are the potential conception dates of Mum

and her two siblings occurring during April and May in 1905, 1913 and 1920.

The little I know about his early life comes

from stories like this one told to me by Uncle George. (Husband of Auntie Ron)

‘He was a runner your granddad, there

used to be a photo of him running…He used to run for money, he was telling me

once about this race with another fella, a sprinter, he kept in the background

while his mates made the bets for him to win. They challenged the sprinter who

said ‘who is it that fella over there, what’s his name…Hall...what’s he done…oh

nothing… I’ll race him anytime. Anyway, this fella and your granddad lined up

and your granddad beat him and won the money’

And these from Auntie Ron

‘Dad bought a radio home from the

exhibition…before that we used to have a crystal set…the cats whisker…a little

bit of crystal and you’d try and get it in just the right spot to hear the

station then someone would come in and jog it. It had earphones and we used to

put them in a big bowl to amplify the sound’

‘We used to go to Ramsgate every year…

we went by coach first of all and then Dad used to hire a car…we used to take

the parrot with us and everything in the back of the car’.

According to family tradition Granddad was

sunk at least twice during the First World War

Auntie Ron remembered

‘Mum said he was torpedoed twice, she

said one time they had to get into small boats and they were adrift for about

eight days…his mother came from a place called Cyprus, I used to think it was

overseas but it was down by the docks…docklands…I didn’t know her much, she,

Mum wasn’t much with his Mum. Mum went there with Dad once; it must have been

after he’d been torpedoed because his mother said to him ‘Oh you’re safe, when

are you going away again’ and that got Mum’s back up…’

In order to find shipping records relating to

him I needed to start with the name of a

vessel that he served on. Crew lists are indexed that way, and not by

individual men’s names. Fortunately I had a starting point. I’d always been

told that Granddad was a stoker on the steamship Port Kembla. The work of a

stoker was a strenuous, dirty and noisy job shoveling coal into the firebox to

run the ships engines

What I learned when I was able to locate a

copy of the crew list was that Granddad was a 'donkeyman', and the only crew

member described this way. As such he was the operator responsible for looking

after the donkey engine in the ships engine room. In the early days of steam

donkey engines powered the deck equipment like cranes and capstans. I’ve

discovered that his skill as a gas fitter (1901 marriage) would have

transferred fairly easily to a 'donkeyman’s' duties. When he wasn’t working on

the donkey engine it is quite likely that he would have had other duties in the

ship’s engine room.

During WWI New Zealand and Australia supplied

thousands of tons of food and essential supplies to Britain when Britain’s

access to these from Europe was cut. Germany's sent its ships into the pacific

to disrupt the supply in an attempt to starve Britain into submission. Despite

the threat merchant ships, like those my grandfather served on, continued to

carry much needed supplies from countries like Australia and New Zealand.

The Port Kembla called into Wellington NZ at

least twice, its last visit was in July 1917. It next appears in my record in

Brisbane, then on to Williamstown, Victoria where it spent at least ten days

loading frozen meat, jams, and wool.

When the Port Kembla left there on September

12 1917 the 59-member crew thought they were headed home probably via Durban.

The Captain knew otherwise though as he had orders to sail to Wellington and

then head back to England, It was as well that they did for just 5 days later

in the last minutes of September 17th and only 11 miles from New Zealand’s Farewell

spit there was an explosion and the Port Kembla sank. If she had gone directly

back to England they would have been in the open ocean when it happened, and

with the radio mast gone and no way to summons help the outcome might have been

decidedly different.

At least that’s the story that I was brought

up with. The reality was a little different, and this is how I know.

At National Archives in Wellington is the

record of a court of enquiry held at the time here in New Zealand and reported

in local newspapers. In the affidavits of the captain and some of the crew the

general impression was that the explosion was caused by a bomb. The chief

engineer though thought the explosion was similar to the one he experienced

when the ship Port Adelaide was torpedoed in February of the 1917. Since

reading that, and thinking about what Auntie Ron said about him being torpedoed

twice, I’ve wondered if Granddad was also on the Port Adelaide when she was

torpedoed, but that remains unproven. The result of the enquiry was that the

sinking of the Port Kembla was the result if an internal explosion by a bomb

likely placed on board by one of the volunteer laborers who loaded it in

Australia. Captain Jack also confirmed that the crew did not know they were

bound for New Zealand. But wait as they say, there’s more.

Then…

One evening as I came in the door from work I

heard the words Port Kembla mentioned on the TV news, and there on the screen

was a group of divers actually swimming down to the wreck. They retrieved the

ship’s bell and some dinner plates which positively identified her as the Port

Kembla. She had been located using the charts from the German Admiralty of

positions of mines laid by the Wolf. Was

this then a case of propaganda because it appears that the New Zealand

government knew the real reason and obviously did not want the general public

to know that the ‘enemy’ had come so close to its shores. Since then a book

about the exploits of the Wolf has been published. The link below is to the dive on the Kembla

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=toLl3V_WJuk

https://divenewzealand.co.nz/travel-165/

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=toLl3V_WJuk

https://divenewzealand.co.nz/travel-165/

The real story is an interesting one. In June

1917 the German mine layer Wolf was in New Zealand waters and laid a string of

35 mines just off Cape Farewell. The mines, set too deep for small craft to

activate, lay in wait for larger quarry. In the wee small hours of the morning

of 18 September 1917 Port Kembla heavily loaded with cargo from Australia fell

victim. The explosion blew a hole in the right side of the hull and destroyed

the radio mast.

As Granddad worked in the engine room of the

ship, this excerpt from the Marlborough Express, Thursday September 20th 1917,

describes what it might have been like for him if he had been on duty.

When it was obvious that she was taking on

water Captain Jack ordered the crew to take to the lifeboats and when he was

sure that the ship was definitely sinking, he and the last two officers jumped

from the ship and swam to the waiting lifeboats. Within half an hour the Port

Kembla was gone. Fortunately, the Steamer Regulus, on a routine run to Westport

along the West Coast of New Zealand, discovered them and took the lifeboats

under tow. There was great excitement in Nelson when the steamer returned

unexpectedly towing the two lifeboats. I still find it hard to associate these much

younger images of him in his flat cap with the elderly grandfather I remember.

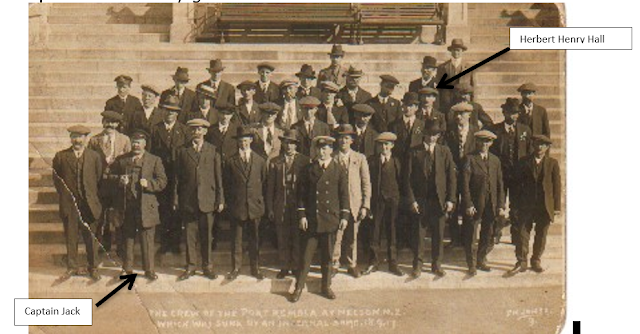

This picture postcard (above) of Granddad and his

crew mates has always been in the family collection. It was taken on the steps of New Zealand’s

Nelson Cathedral. The picture below was taken some time later in front of a Nelson Hotel.

In the few days they were there the crew were ‘hospitably entertained’ by the citizens of Nelson. Local companies supplied them with tobacco and pipes, made vehicles available so that the men could be driven through the Waimea and around the “three bridges” ending with afternoon tea at Brightwater.

With nothing else to add to this part of his

story I decided to email the Shipwrecked Sailors Society of New Zealand to try

to find out what happened next. This was the reply.

I had already found his CR10 at National Archives (UK) but this was the first time I had heard of DSBs, unfortunately there are no records of DSBs

Another part of the same family story about the sinking of the Port Kembla was that when he had been pulled aboard the lifeboat Captain Jack said to the men ‘Your pay stops now’ and according to Auntie Ron, Nan was pretty bitter about that. I have since learned that that was part of any crew agreement of the time. Up until then I hadn’t really given any thought to how Granddad, now a Distressed British Seaman, might have survived stranded half way around the world without income. I was soon to find out how he did.

The repatriation arrangements for a

circumstance like the PORT KEMBLA would be for the company staff (officers/engineers

etc.) of the Commonwealth and Dominion Line to be placed on the first available

company vessel that could take them, and the balance of the crew(non-company

contract) would be regarded as Distressed British Seamen(known as DBS's) and

any other British ships would be obliged to take as many as they could (this

would be up to the lifesaving capacity as ships were licensed for the carriage

of so many "souls").

I had already found his CR10 at National Archives (UK) but this was the first time I had heard of DSBs, unfortunately there are no records of DSBs

Another part of the same family story about the sinking of the Port Kembla was that when he had been pulled aboard the lifeboat Captain Jack said to the men ‘Your pay stops now’ and according to Auntie Ron, Nan was pretty bitter about that. I have since learned that that was part of any crew agreement of the time. Up until then I hadn’t really given any thought to how Granddad, now a Distressed British Seaman, might have survived stranded half way around the world without income. I was soon to find out how he did.

My email enquiry was forwarded on to several

other people, which produced this result

Lynton Diggle, the man who wrote the 8th Edition of NEW ZEALAND SHIPWRECKS had a crew list of the PORT KEMBLA and he passed it on to Mike Fraser (who you may know) and the list shows that H.H. Hall signed on the collier NGAHERE which was in regular running from Westport to Wellington and other ports. It was likely there were no immediate berths available on British ships out of Wellington and your Grandfather probably decided that he could earn wages and have accommodation in the meantime and when the NGAHERE returned to one of the major ports he could check on the availability of passages home and act accordingly. As a result of this diversion it is going to be well-nigh impossible to find what ship he eventually returned to UK on.

Lynton Diggle, the man who wrote the 8th Edition of NEW ZEALAND SHIPWRECKS had a crew list of the PORT KEMBLA and he passed it on to Mike Fraser (who you may know) and the list shows that H.H. Hall signed on the collier NGAHERE which was in regular running from Westport to Wellington and other ports. It was likely there were no immediate berths available on British ships out of Wellington and your Grandfather probably decided that he could earn wages and have accommodation in the meantime and when the NGAHERE returned to one of the major ports he could check on the availability of passages home and act accordingly. As a result of this diversion it is going to be well-nigh impossible to find what ship he eventually returned to UK on.

Ngahere

I leaned that the crew lists for the Ngahere are

held at National Archives at Kew, unfortunately they aren’t digitised, I can

definitely feel another visit to Kew coming on. When we did go to there I

Immediately ordered document BT 110/5821/ 1, then used the half an hour before

it was available to do a bit more digging.

It wasn’t until I was writing Granddads story

that I carefully re-read all the material that I had accumulated about him,

including his CR10 and merchant Marine Medal cards. You’d have thought, considering how long I

have been working on my family history that I would have done that years ago

wouldn’t you, and gleaned as much as I could from his record as I could…? The

answer to that was a categorical no I had not!

The CR10 was his registration documents as a seaman

employed in the Merchant Navy. Apart from minimal personal details about him,

and a small photograph, it should also have the official number of the ships

that he served on. From those entries I had correctly identified the Gaelic

Star, Celtic Star, Gothic Star, Star of Victoria, and Port Alma. More about

them a bit later, what I hadn’t taken much notice of, admittedly on a different

page to the numbers and without any identifying number of its own , was written

what looked like ‘Pr Sydney 9.8.19’. In

actual fact it was the name of a ship called the Port Sydney that I had

overlooked, and my thinking that it referred to the Australian port of Sydney

was completely wrong.

The oversight of the words Pr Sydney could

have left a much bigger gap in my knowledge about him. In that spare half an hour while waiting for

the Ngahere’s documents we located and ordered two more sets of documents,

including those for the Port Sydney dated 1919 and 1920.

I was so disappointed in the information

about the Ngahere because it did not contain a crew list. The Port Sydney on

the other hand was a winner. There he was in the 1919 crew list, and what a

bonus that find was, because it also named his previous ship. With the help of

an archivist we were able to identify it as the Ulimaroa. Unfortunately, as

with the Ngahere the documents held at Kew did not contain a crew list. Nor was

he within the crew list for the Port Sydney papers dated 1920. So if I put all

the information together that I now know about some of his time as a merchant

seaman it looks like this

Port Kembla left England on April 29 1917 sunk

September 1917 off the coast of New Zealand

Ngahere, a collier plying between New Zealand

ports.

Ulimaroa, which according to information I

was able to locate was originally a passenger ship, but in January 1916 it was

requisitioned for the remainder of the war, by the government of New Zealand to

transport troops to England, India and Egypt. Following the armistice, ULIMAROA

was used to repatriate wounded soldiers back to New Zealand, making her final

departure in this capacity from Suez on 30 June 1919, and arriving in Auckland

on 8 August.

Port Sydney, its crew list shows his sign on

as 29 April 1919 in Sydney and his sign off at Victoria Dock London 19 July

1919, this doesn’t quite marry up with the notation in his CR10 of Pr Sydney

9.8.19. He does not appear in the only other crew list for that vessel that I

located at Kew, dated 1920. I can’t imagine that the ship would not have sat

idle for many months so perhaps there was another voyage.

There follows a gap between the Port Sydney,

1919 and the dates that are written in his CR10

Ship number 140302 (Gaelic

Star) date 18 July 1922

Ship number 13469 (Port Alma) date 29

December 1922

Ship number 108793 (Gothic

star) date 21 September

1923

Ship number 132046 (Star of Victoria) date 29

January 1924

Then there is the official stamp of the

Celtic Star with a date 1 September 1924, but no indication whether it relates

to a sign on or off.

According to some of the documents I found at

Kew the ships that Granddad sailed on visited various international ports

including; Balboa, Newport News (USA), River Plate and various ports in

Australia and New Zealand.

I remember hearing about some of the souvenirs

he brought home from his travels. One was a parrot, someone taught it to call

out “Mrs. Hall, Mrs. Hall”, which would bring Nan running to see who it was

that was calling her.

Another time he came home with a tiny Marmoset

monkey, no quarantine regulations then. Its fur was very dark except for the white

tufts on its ears. It wore a knitted little cap and jacket to help keep it

warm. When it was very cold it would sleep in the cooling oven for a bit of

extra warmth.

Only Nan appears on the electoral roll for

1938 at 16 Ford Street, Poplar, so Granddad was likely still at sea, he would

have been 59 years old.

According to Uncle George (Auntie Ron's husband) Granddad had a

‘shore job’ during the Second World War with the Blue Star Line, this is borne

out by his occupation on the 1939 register. He would have been about sixty years

old and Nan about fifty six.

Granddad, occupation ships stores (donkeyman)

and son young Herbert Henry, occupation Railway (elec) Maintenance) appear

together on the 1939 register at 21 Beckton Road, Canning Town. But was no

sign of Nan. Despite trying every search combination of her name and birth-date

I just could find her on the register. There was however a redacted line in the same family, which when I contacted the company that managed the register turned out to be her, and the entry was un-redacted.

My cousin Sheila Storey, daughter of Mum's brother, says that when she

and her oldest child were evacuated to Wales Nan went with them. When we look

at some of the events that occurred in that year we can see why.

March 17 the chamberlain denounces Hitler and

recalls British ambassador to Berlin.

April 5 Britain is bracing itself for war

with immediate plans to evacuate 2,500,000 children should hostilities begin.

June 3 Britain’s first military conscripts are enrolled.

November 13, first bombs dropped on British

soil, in the Shetlands and later in the month German planes drop mines in the Thames

estuary

Nan was also without him on the 1945

electoral roll still at 16 Ford Street, Poplar. Which makes me wonder if he would have still

been at sea, then aged 66? And was he absent when my parents married by special

license in February 1942. Questions I am unlikely to ever know the answers to.

I then lose track of him until he, with my

grandmother, mother, father and sister depart for New Zealand on board the

Tamaroa in 1949. But that is another story